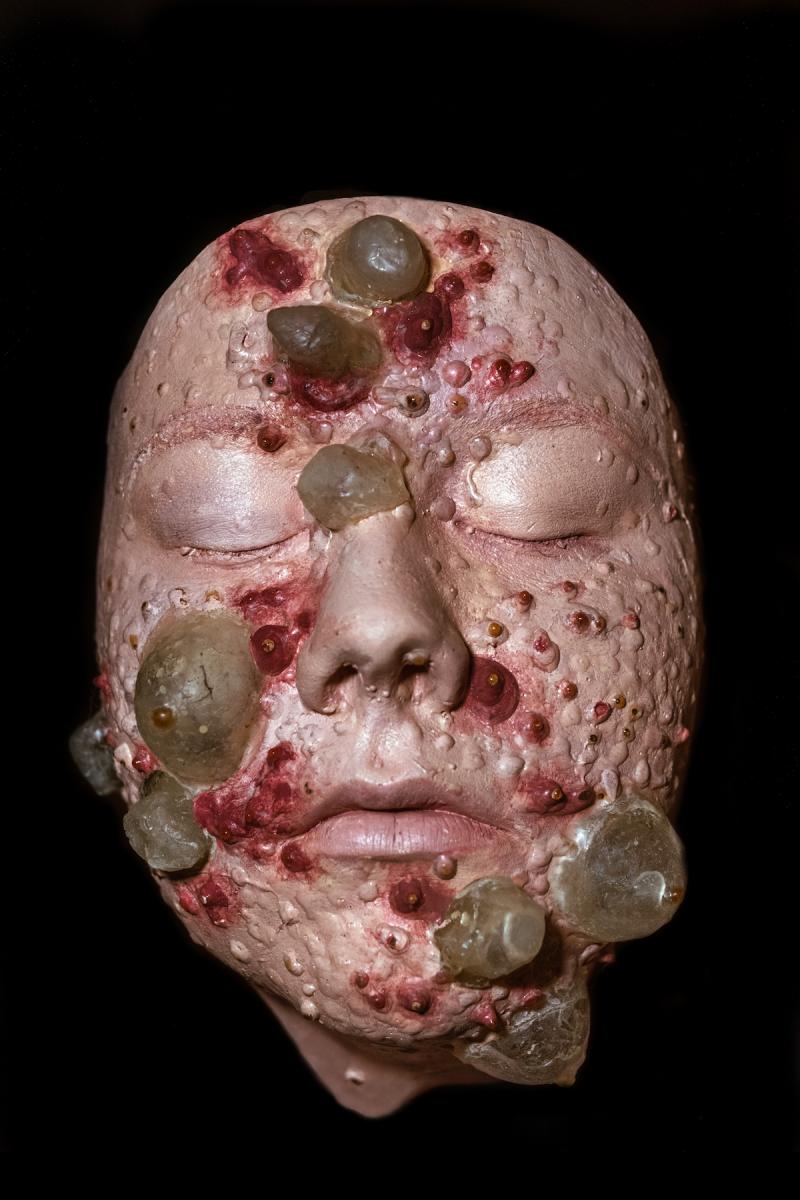

(December, 2018)

9”x7”x4”

Artist’s Statement

Miasma was created as an attempt to characterize the novel, contaminated biosystem created by the disruption of the San Jacinto River by the release of industrial waste containing known toxins. Through its graphic depiction of the potential physiological impact on resident humans, Miasma incorporates a cross section of the beings affected by this change as well as the culpable toxin itself. Though the social and environmental dynamics of this pollution cascade are well-documented in Houston media and EPA and FDA documentation, its surrounding discourse is relatively inaccessible to those most affected. By exhibiting this piece in a local (free) gallery, I hope that Miasma is able to bridge this gap: through viewers’ exposure to the piece itself, they are able to gain knowledge on the their own exposure to the enclosed chemicals in their day-to-day lives. The process of creating Miasma, producing a cadaverous cast of my own face only to hollow it out and imbue it with living, stinking, and dangerous materials was a distinctly unique, fraught experience. Excavating chunks of my cheeks, chin, and forehead, I embedded resin boils as if looking in a mirror before piercing them with a syringe of algae, amoebas, and dioxin. My face transformed in an artificial acceleration of the process many Houston residents may be going through over the course of months. With time, the encapsulated water may leech into the integral material of the sculpture, and my face will crumble: a sobering, discomfiting assertion that this change is both irreversible and catastrophic. As this decay progresses, Miasma will grow in similarity to its companion piece. Myco, asserting the progression of decomposure and regrowth (and eventual global fungal takeover), is a much truer death mask than Miasma with its cross section of a biosystem. The two do not act in sequence, or dichotomously, but as two alternate and mutually exclusive forms of existence dependent on systems of living and non-living beings. |

A Toxic EcologyThe release of dioxin and other toxins into the San Jacinto River via industrial waste has created a new and transformed biosystem, livable for some and not others, that has drastically altered the nature of the relationships among living and non-living beings. These irreversible effects have acted unevenly on multispecies communities, simultaneously building coalitions and disrupting established symbioses, destroying and creating relationships, and inflicting harm on individuals. They have been distributed and responded to differently as a result of social and natural factors in the neighborhoods and ecosystems surrounding the river, impacting those responsible for their release as well as innocent bystanders.

There is life in the water. Some community members flourish in these altered conditions, taking advantage of reduced competition or a higher tolerance to disturbance [1] . Green algae blooms as its consumers dwindle; some microorganisms thrive in the resultant stagnant, hyper-oxygenated water. Human residents and water birds eat the fish pulled from the water, who in turn eat each other and benthic invertebrates. There is waste in the water. Solid, toxic waste flows from the Highland Acid Pits Superfund site upriver. Emissions from petrochemical plants contain 1,3-butadiene, shown upon investigation to be connected to a higher incidence of leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia, and acute myeloid leukemia in human children [2] . These findings were labelled complicated by governmental parties and deemed an association instead of a causal relationship. Poorly planned waste impoundments from a paper mill in the 1960s have been releasing polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (dioxins) [3] and polychlorinated dibenzofurans into the river as a result of physical site changes: groundwater extraction-triggered land subsistence [4] have caused the waste pits to become submerged and permeated, forming the San Jacinto River Waste Pits Superfund Site [5] . The dioxins released from the SJRWP Superfund Site are bioaccumulative [6] , taken up by the aforementioned benthic invertebrates and building up increasingly in bottom dwellers and upward in trophic levels until fish are consumed by humans. Because of this bioaccumulation, higher trophic level animals [7] are faced with the highest concentrations of dioxin; this includes native fish, such as the black drum and the larger mullet that eat blue crab and clams off the river bottom, and the humans that eat these fish. Contact with dioxins via direct contact, incidental ingestion, or fish consumption leads to human health risks deemed ‘unacceptable’ 6 by the EPA, causing widespread disruption [8] of organ system development within the vertebrate body. In the short term, dioxin exposure results in skin lesions such as chloracne and patchy darkness as well as long term immune system impairment. Dioxins and other toxins also act on the community level. For years, cancer clusters have been recorded in East Harris County neighborhoods bordering Superfund sites. A panel [9] of Texas health officials has decided not to investigate these cancer clusters or test human tissue dioxin levels amidst community pushback around the SJR Waste Pits continuing release. Texas regulators have located and documented thirty hotspots along the San Jacinto River where dioxins have settled around residential areas, but have declined to test wellwater or disclose the location of these hotspots to the public. Alternate strategies for responding to dioxin dump have been proposed; in a debate between removal and containment, social equity distributive impact dynamics are critical in deciding how waste ends up where it does and whether or not it stays there. Power determines susceptibility to and likelihood of contamination.

This relationship is clear when looking at who has been affected by and has affected in turn the contamination of the San Jacinto River. Some community members are more susceptible to contamination while others are more likely to contaminate; industrial leaders in the ‘potentially responsible parties’ are responsible for the initial dumping, while EPA regulators make the decisions on how or if to clean it up. Subsistence fishermen that can not afford to stay within the safe limits of seafood consumption or adhere to bans, people living around the river that are poorly represented politically and were denied their requests for groundwater and well-water testing and correlational studies with released dioxin and the observed cancer clusters are human residents currently facing the greatest individual and community alterations. Champion Coated Paper Co. installed the waste pits, delivering jobs and economic growth and poison to the region. Sean Matula, a Baytown resident, has been at the center of the local dioxin controversy: financially able to have his family’s well water tested and socially able to garner media attention when revealing its high dioxin levels and his resulting health issues. Scott Pruitt, Administrator of the EPA, directly authorized armored cap installation 6 in SJRWP for dioxin covering and containment. Miasma utilizes contamination, corruption, adaptation, death as schemas for enacting and reacting to change in an environment, facing dynamics that are formed from cascades that happen because of an initial shift (extraction, dumping, climate change, fire) where the toxin itself too is a key player. Contamination is a relationship, a two-way dynamic; mass changes in ecosystems such as those wrought by ground removal or paper mills cause physiological and social change on residential humans such as displacement, illness, and the loss of livability. Miasma incorporates the agent of change itself into the piece, using contaminated San Jacinto River water and its associated flora and microbiota, now most likely dead. Other human residues, like shells from a midden, other chemicals, microplastics, broken down pier-wood and building materials are unavoidably included. It addresses what life might look like in an altered system, how the release of these toxins has created new albeit damaged communities and incorporating this relationship into the sculpture to elucidate the effect of the suspended/dissolved/bioaccumulated toxins on human and non-human life forms and how these effects build on each other. |

<< 0. Home/Introduction ----- 2. Infrastructure >>

[1] White, Sally S., and Linda S. Birnbaum. “An Overview of the Effects of Dioxins and Dioxin-like Compounds on Vertebrates, as Documented in Human and Ecological Epidemiology.” Journal of Environmental Science and Health. Part C, Environmental Carcinogenesis & Ecotoxicology Reviews, vol. 27, no. 4, Oct. 2009, pp. 197–211. PubMed Central, doi:10.1080/10590500903310047.

[2] Horswell, Cindy. “Study: Children Living near Houston Ship Channel Have Greater Cancer Risk - Houston Chronicle.” Chron, 18 Jan. 2007, https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/article/Study-Children-living-near-Houston-Ship-Channel-1544789.php.

[3] Iyer, Rupa, et al. “A Review of the Texas, USA San Jacinto Superfund Site and the Deposition of Polychlorinated Dibenzo-P-Dioxins and Dibenzofurans in the San Jacinto River and Houston Ship Channel.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 23, no. 23, Dec. 2016, pp. 23321–38. Springer Link, doi:10.1007/s11356-016-7501-8.

[4] Broyles, William. “Disaster, Part Two: Houston.” Texas Monthly, Dec. 1974, https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/disaster-part-two-houston/.

[5] US EPA, REG 06. “San Jacinto River Waste Pits Superfund Site.” US EPA, 17 Feb. 2016, https://www.epa.gov/tx/sjrwp.

[6] Dioxins and Their Effects on Human Health.” World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dioxins-and-their-effects-on-human-health. Accessed 13 Nov. 2018.

[7] Usenko, Sascha, et al. Defining Biota-Sediment Accumulation Factors for the San Jacinto River Waste Pits, Texas Final Report. Baylor University.

[8] Gatehouse, Robyn. “Ecological Risk Assessment of Dioxins in Australia.” Technical Report: Department of the Environment and Energy, no. 11, May 2004, https://www.environment.gov.au/protection/publications/dioxins-technical-report-11.

[9] Carroll, Susan. “Panel Says ‘No’ to More San Jacinto River Cancer Studies - HoustonChronicle.com.” Houston Chronicle, 9 Sept. 2015, https://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/health/article/Panel-says-no-to-more-cancer-study-6492157.php.